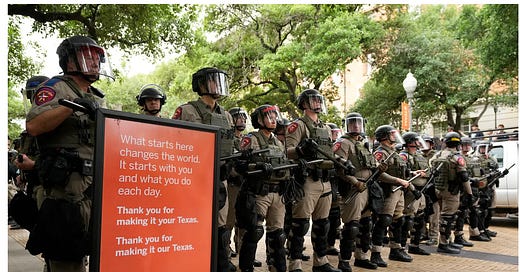

A group of students assembled on the University of Texas at Austin campus to call for an end to the war in Gaza. They did not engage in violence. They did not disrupt classes or occupy administrative buildings. They set up tents on a lawn. They were met with a militarized response, ordered by Governor Abbott, and supported by University administrators. Students and journalists were arrested. Mikala Compton/American-Statesman

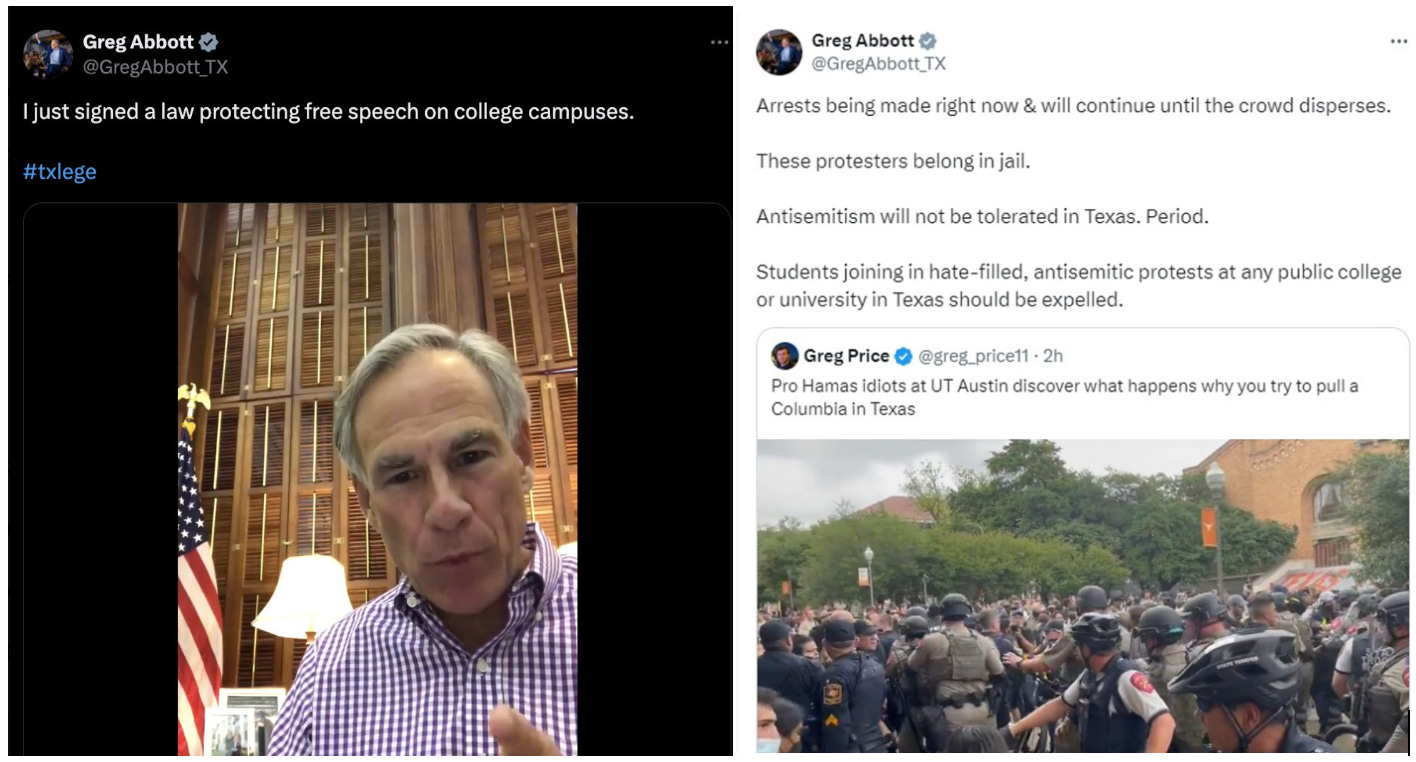

Greg Abbott is one of many on the right that has bemoaned the death of free speech on campus. He signed a law to protect such speech in 2019. And then he calls for peaceful protestors to be arrested.

So how can Abbott justify such a reversal to his call for free speech? The protestors are anti-semitic, he says. Really? How does Abbott and the police wading through the crowd know the students are anti-semitic? Because, as Dave Weigel points out, Abbott has broadened the definition of anti-semitism to incorporate support for a Palestinian state. Any protest for this cause is, therefore, anti-semitic, and therefore worth contravening his commitment to free speech, which, lets face it, was never meant to be especially binding.1

The legal basis of the police sweep of UT-Austin was dubious. Amy Sanders, a journalism professor and lawyer pointed out that UT has a policy that allows public assemblies, and there is no credible evidence that the assembly threatened public safety. So what was the point? Per Sanders:

The point is absolutely to intimidate the students and other protesters into not exercising their First Amendment right to speak. The whole goal of sending in riot police, of making the statements that the governor of Texas made, is to chill freedom of expression. It is to make clear that you don’t approve of their views, and that you will attempt to punish them for expressing their views—even if what they’re doing is protected by the First Amendment. It’s an extremely effective tactic.

All charges were subsequently dropped, because there was no compelling basis to charge people for “trespassing” on an open space in an open campus. Nevertheless, the university still told the arrested students they could not return to campus based on a new policy where “arrested for trespassing” became a violation, even if it was not prosecuted. Seemingly, university administrators were making it up as they went along, but consistently overreacting in their zeal to punish protestors.

The absurdities that follow are almost funny. The University of Austin, the pretend university launched by IDW types like Bari Weiss, is preparing its “Forbidden Courses” for the summer. It stands silently by as the actual University of Texas at Austin is censored, safe in the knowledge that they are regime-approved.

You don’t have to be blind to the real cases of anti-semitism in America to be troubled by accusations of anti-semitism to shut down the most visible protests to a military response that has become increasingly unpopular. The looking glass nature of the argument is reflected back at us: senior Israeli officials who oversaw the destruction of every university campus in Gaza complain that what is going on American campuses is unacceptable. Tarring every objection to Israel as anti-semitism makes it harder to address actual cases of this malign worldview, which unfortunately is not in short supply.

There are the protests, and what the people off campus want to turn the protests into: sites of disorder and violence, a basis by which to discredit and control campuses, a reason to fear leftists radicals, and a campaign issue in the presidential election. For them, the George Floyd protests of 2020 were events of failure, of an insufficient will to crack down on dissent. (Though police did indeed crack down). They want the police to intervene aggressively, and with a sense of righteousness that comes from claiming to be on the right side of history.

But in places where the university administration has not responded aggressively, protest tactics of the kind used in Texas and Columbia have not created unrest. Overwhelmingly, the actual experience of protests on campus has not been one of violence, as Harvard professor Ryan Enos noted:

Some claim that universities are overrun with antisemitic hordes, while others, including myself and my colleagues, have seen only peaceful actions from diverse student protesters, including many Jews, earnestly challenging what they see as a grave violation of human rights. University leaders must be clear about what is happening on our campus, rather than letting social media and opportunistic politicians manufacture narratives.

The most widely cited examples of anti-semitism on campus are actually occurring off campus, and likely perpetuated by by non-students. While this distinction is of little consolation to Jewish students who feel targeted, it does matter for how the public understands what is happening and how authorities respond to the events. University leaders are blaming “outside agitators” for infiltrating the campus. An Emory spokesperson said “these individuals are not members of our community.'" But when police are arresting professors, the idea that the militarized response is targeting outsiders falls apart. For example, an economics professor at Emory walked up to police who were arresting a protestor asking “what are you doing?” She explains, in vain, that she is a professor as she was assaulted by two police officers. She was then arrested, and charged with battery for assaulting the officer. (Video).

When Speaker Mike Johnson went to Columbia, and called for the national guard to be deployed on campus, the goal is to create disorder, not quell it. The student protestors are not sufficiently violent, but the images of police or soldiers wading in to crack a few heads creates its own justification. Adam Serwer in The Atlantic explained this logic:

As we approach the summer of 2024, the economy is growing, migration to the border has declined at least temporarily owing to what appears to be a new crackdown by Mexican authorities, and in many major cities, crime is returning to historic lows, leaving protests as the most suitable target for demagoguery. The Biden administration’s support for Israel divides Democrats and unites Republicans, so the longer the issue remains salient, the better it is for the GOP. More broadly, the politics of “American carnage” do not work as well in the absence of carnage. Far-right politics operate best when there is a public perception of disorder and chaos, an atmosphere in which the only solution such politicians ever offer can sound appealing to desperate voters. Social-media bubbles can suffice to maintain this sense of siege among the extremely online, but cultivating this perception among most voters demands constant reinforcement.

As a faculty member, how do I see this? What is at stake is whether university communities can exercise autonomy over how they establish norms on campus. For the last decade we were told the norms were not supportive of speech. Now the same people are urging arrests as a result of speech.

If elected officials want to pass laws, there is not much to do about it. But when university administrators preemptively surrender to bad-faith officials like Stefanik and Abbott, and invite a militarized response onto their campus, they have given up on the idea that they are leading a community based on shared norms. What will be the long-term fallout for the campus community when students and faculty have been assaulted and arrested by police? Such actions will undermine trust in the long-run, and in the short-run will just fuel more student protest. The practice of pitching tents on university lawns was, apparently, an unacceptable affront to the authorities, a key to getting public attention to the war. Pro-Palestinian groups quickly expanded this tactic, and more police will be sent to respond.

What is disturbing is how many university leaders have decided that the appropriate response is to copy what UT-Austin and Columbia did, which is the militarize the response despite the dismal outcomes that followed. Protestors have been met with riot police despite not rioting, and subjected to tear gas and rubber bullets. The collective mismanagement of the situation is baffling. It is as if university leaders have internalized the idea that they were too receptive to protests in 2020, and now need to prove that such tolerance no longer exists. When the smoke clears, they will be left leading campuses with students and faculty that despise them.

Universities can be slow and bureaucratic. They can fall prey to excesses. But I trust them far more to police and correct those excesses than I trust those who are attacking them now. In the long run, student protests are often unpopular in their own era, but have a pretty good track record of being right about major issues of conflict, such as Vietnam, civil rights, apartheid in South Africa, or the war in Iraq. The students in Austin should retain mementoes of their arrests for when the university runs a retrospective event applauding their courage decades from now.

Get ready for a new wave of opinion pieces about how campus unrest reflects how universities have become sites of indoctrination, how the protest is driven by neocolonial teachings, about the narcissism of today’s students and faculty.

This claim does not hold up the close scrutiny. It seems obviously implausible to believe both that new pedagogies has fundamentally changed how students interpret conflicts that involve the US, and that students of a previous era would have ignored the conflict in Gaza. The war in Gaza is globally very unpopular and in the US increasingly unpopular. Yet so many cannot understand student protests without resorting to the indoctrination arguments that the far right have made about higher education, which were made to discredit higher education while denying the students agency.

These critiques serve two purposes. First, they erase the subject of the protest. The fundamental question of whether the protestors have a point is elided. It cannot be acknowledged that a great many people, not anti-semitic, not in thrall to Marxist theories, are deeply troubled by a a massive death toll in Gaza, and a deepening conflict in the Middle East, and their government’s role in this conflict. Many of these people are Jewish students and faculty. They have a right to be heard.

Here is a very simple test: The next time you read an opinion piece about protests on campus, check if the author bothered to engage in the basic question of what the protest is about: should the war continue, and whether the US government should continue to provide arms for it?

It says something truly profound about the blinkered view of the American pundit class that they only way they can understand a real war is through their own worn culture war framings. They squint just enough to be outraged by the fact that students are protesting but refuse to engage in a discussion of what the students are protesting about.

Second, they serve to delegitimize the university itself. I’ve written about the tactics of delegitimzaiton, deconstruction and control before in the context of the administrative state, but it applies just as well to universities. As the work of political scientist Dan Carpenter points out, public organizations win autonomy based on building positive reputations; they lose that autonomy when they become viewed as incompetent or immoral. Creating reputational damage is a necessary precondition to justify removing autonomy from institutions. The narrative of a woke or disorderly campus justifies removing faculty or student input on who leads the institution, of legislators or donors establishing the contents of the curriculum. Those pushing that narrative will use any campus event to further it. Far too many people who should know better have gone along with it.

This is one of the ways that what is happening on campuses now links to the campus speech wars, the censorship of speech related to race and gender, and removal of DEI offices, and the erosion of faculty and student governance. Universities, as a community, are permitted less and less to manage themselves based on their values. They will not be trusted to find the right balance. Who governs in their stead? Is society better off with Elise Stefanik’s vision of higher education?

Most of the social media I quote here, apart from the Abbott tweets, comes from BlueSky, which has provided more thoughtful analysis of what is going on than Zombie Twitter.

As a retired academic I agree with your discussion. I remember the campus protests of the Vietnam War as well as the other protests you mentioned. I was also appalled by the blame placed on the Kent State protestors. Republicans only want free speech when it aligns with their views. As long as the protestors do not violate the rights of others and do not damage property I'm all in favor of their protests. How can anyone learn to be a citizen without direct participation. I do think that universities, the media and the press have to be careful to separate student protests from the actions of non-students who use the protests for their own purposes. I also agree that such actions will only increase the resolve of student protestors and will probably lead other students to join in.