Making SNAP Interviews More Flexible Increases Take-up

A tangible thing that state and local governments can do to maintain safety net access

The incoming Trump administration has promised to reduce regulatory burdens, but with a focus on businesses rather than individuals. Indeed, Trump’s first term was marked by efforts to make safety net programs less accessible. His supporters plan to add more work requirements to programs like SNAP (also known as food stamps) and Medicaid as a way to offset the cost of Trump’s proposed tax cut extensions, despite evidence that these work requirements mainly serve to deter eligible claimants from accessing benefits.

If Trump was serious about reducing burdens, a good place to start that would help a lot of Americans would be to relax SNAP interview requirements, which are imposed via USDA regulations rather than law, and thus ripe for a post Chevron re-evaluation. More realistically, state and local governments can find ways to help applicants manage these and other administrative checkpoints.

Mandatory interviews are a critical administrative checkpoint in SNAP: a hurdle that many people stumble on, but which states are required to incorporate into their eligibility processes. New research points to ways that states can structure those interview processes to increase interview completion and take-up.

There are two types of reasons an applicant can be denied for SNAP. Applicants denied for ineligibility do not qualify based on the program rules - for example, they might make too much money. Applicants who are procedurally denied did not complete a required step in the process, such as submitting verification of job income. In other words, procedural denials reflect a failure of the process to determine eligibility. In an ideal world, denials would only be for ineligibility, and not because determining eligibility proved too difficult.

Not completing the required interview for SNAP is one of the most common reasons for procedural denials. In many places, applicants have no control over the timing of the interview. They are assigned a time and mailed a notice saying to expect a call from an eligibility worker around that time. As might be expected, this approach poses special challenges for people who work during business hours, parents of young children, and those who lack stable housing. A not infrequent complaint is that people get the mail notice after their interview time has passed. And if they fail to complete their interview within the 30 day application window, they have to start the application all over again.

There are no penalties for high procedural denial rates. As a result, many agencies do not measure and monitor them carefully. Some are even surprised to learn that denials due to a failure to complete interviews are more than double the share of those for missing income verifications. In a few places, the share of denials due to interview failures is larger than denials due to ineligibility (in Missouri, the share of denials due to failure to interview was around 50%). In another program, Medicaid, about 7 out of 10 people who lost coverage after the pandemic did so due to procedural denials.

Procedural denials not only prevent people from getting access to benefits, they are also a source of inefficiency for the government agency. People who are procedurally denied will submit the same paperwork multiple times, which may often involve the same employees tasked with completing interviews. The failure to get the determination right the first time generates more work both for the applicant, and for the government.

Agencies cannot simply eliminate interviews, but they can make them easier for applicants to manage. One way to do so is to make the interview option more flexible, and better communicate interview options to clients. Flexible interviews, in which applicants are given a scheduled time, but can also call in to complete their interview at their convenience, increases access to SNAP.

In two separate studies, Code for America, a civic tech nonprofit, partnered with academic researchers at Georgetown, NYU, Johns Hopkins and Michigan to evaluate the impact of moving to a flexible interview process in Los Angeles (publication, ungated) and Boulder, Colorado in rigorous randomized experiments. The full research teams are ourselves, Tatiana Homonoff, Gwen Rino, Jason Somerville, Jae Yeon Kim, Pam Herd, Sebastian Jilke, and Kerry Rodden.

The results were strikingly consistent: In both places, about half of the people who were offered the flexible interview option chose to use it. In Los Angeles applicants given the flexible interview option (not just those who used it) had 30 day approval rates that were 6.2 points higher than those who were in the status quo scheduled interview-only process. In Boulder, applicants texted about a flexible interview option had an approval rate that was 6-7 points higher than those who only received a mailer with a scheduled interview time.

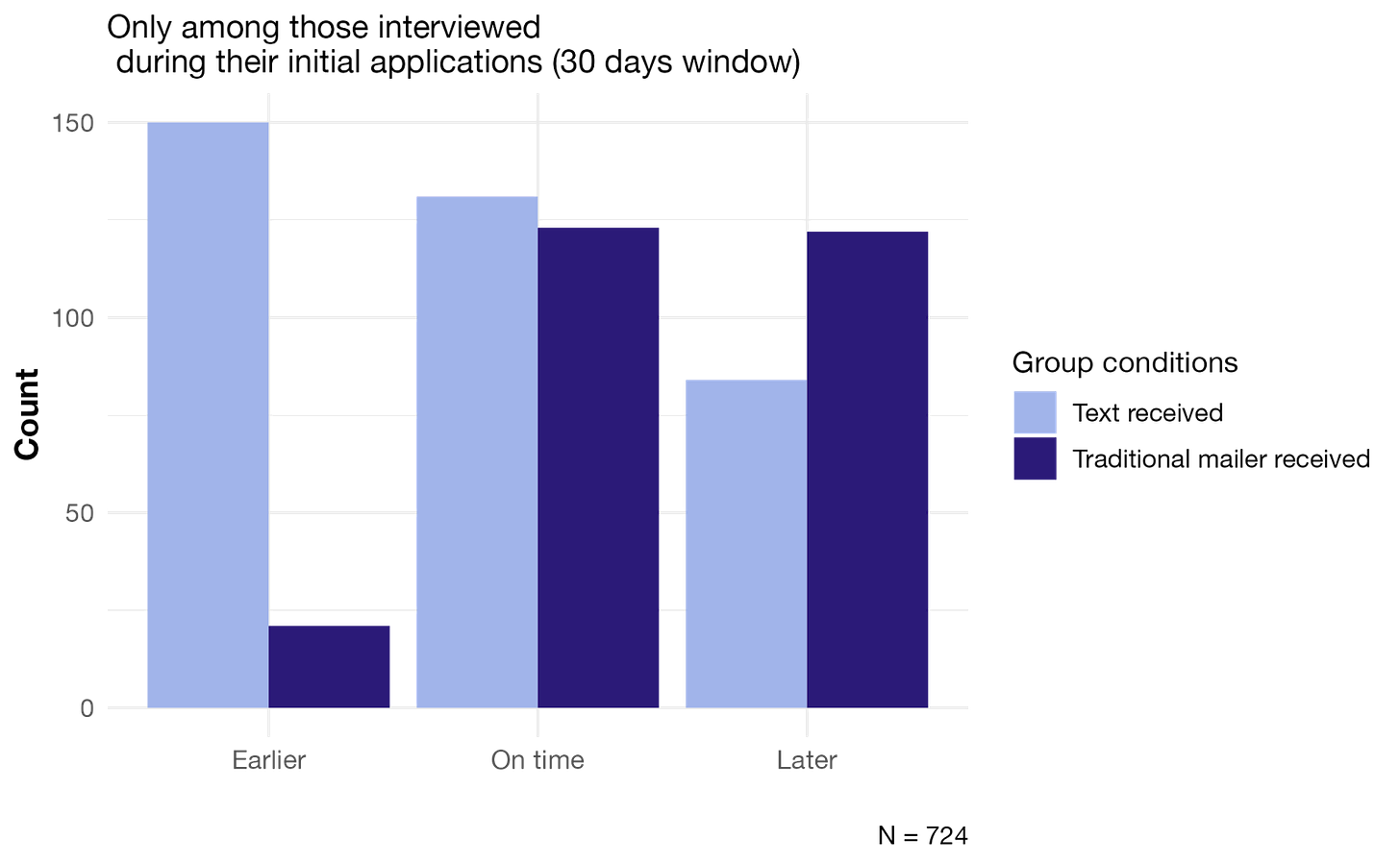

These changes in overall approval rates do not capture the whole story though. First, people who were offered the flexible interview option tended to complete their interview earlier and receive benefits sooner (Figure 1): 3-4 days earlier (in Boulder) and 4 days earlier in Los Angeles. In Los Angeles, among people who might have been considered expedited, or having especially time sensitive circumstances, the approval rate within five days of applying doubled (status quo: 13.7%, flexible interview: 27.6%).

A follow-up survey in Boulder found that applicants who were sent texts were much more likely to say they knew what to do to complete their interview compared to those who only received mail notices with their scheduled interview time. The reduction in denial rates and the faster time to approval represented an increased value of applying to SNAP of nearly $100 over the initial six month benefit period for those who have access to the flexible interview process.

Figure 1: People offered a flexible interview option tend to complete their interviews earlier than those who only get a scheduled interview (Boulder)

In addition to improving access for eligible applicants, there were also time and cost savings for the agencies implementing these changes. In Boulder, those offered the flexible interview option were over 10 points more likely to complete their interview, which means caseworkers make fewer calls with no answer and clients make fewer calls to reschedule missed interviews. And adding texting is comparatively cheap - in Boulder, sending information via text was 1/38th the cost of sending it via mail.

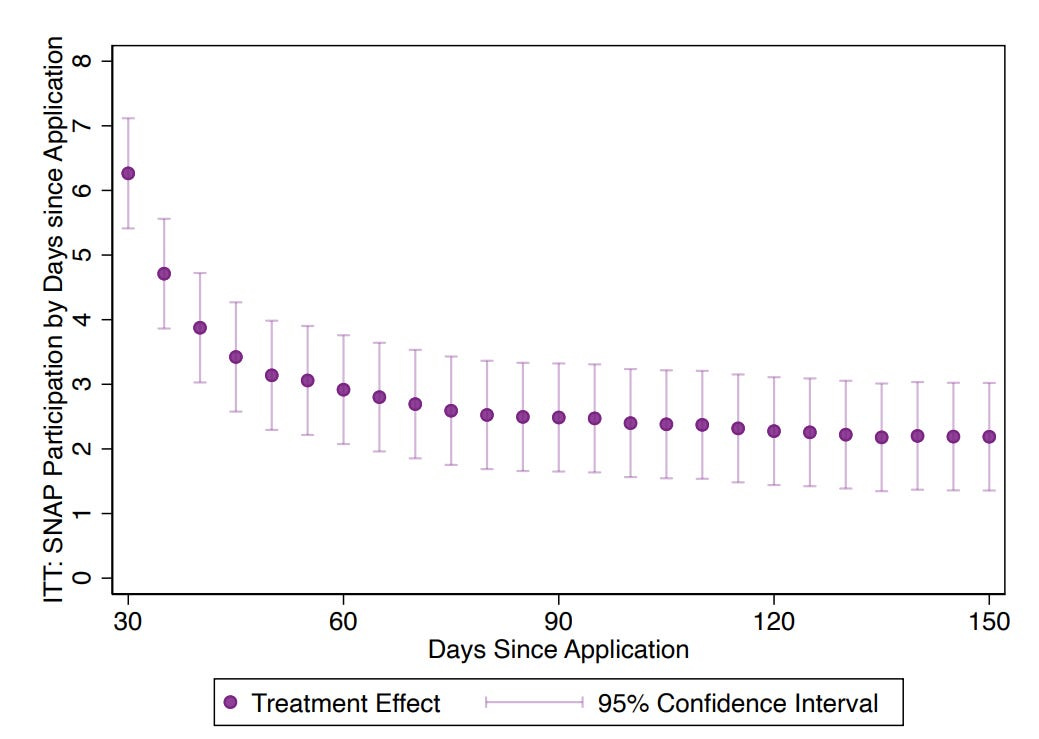

Lower procedural denial rates also means fewer reapplications. In Los Angeles, the difference in approval rates between the flexible interview and status quo conditions shrank from 6.2 points at the end of the 30 day enrollment period to 2.2 points after five months (Figure 2), indicating that many people who were denied initially applied again and were approved. This represents a lot more work for the County compared to simply completing the interview for someone’s first application. In fact, these efficiency savings were so clear to administrators that flexible interviews have been implemented across all of Los Angeles County. Boulder also adopted flexible interviewing processes, partly in order to reduce the inefficiency of missed interview assignments for caseworkers.

Figure 2: In Los Angeles, the gap in receiving benefits shrinks from the 6.2 points after 30 days to 2.2 points after 150 days, indicating that many people who are procedurally denied apply again and get approved

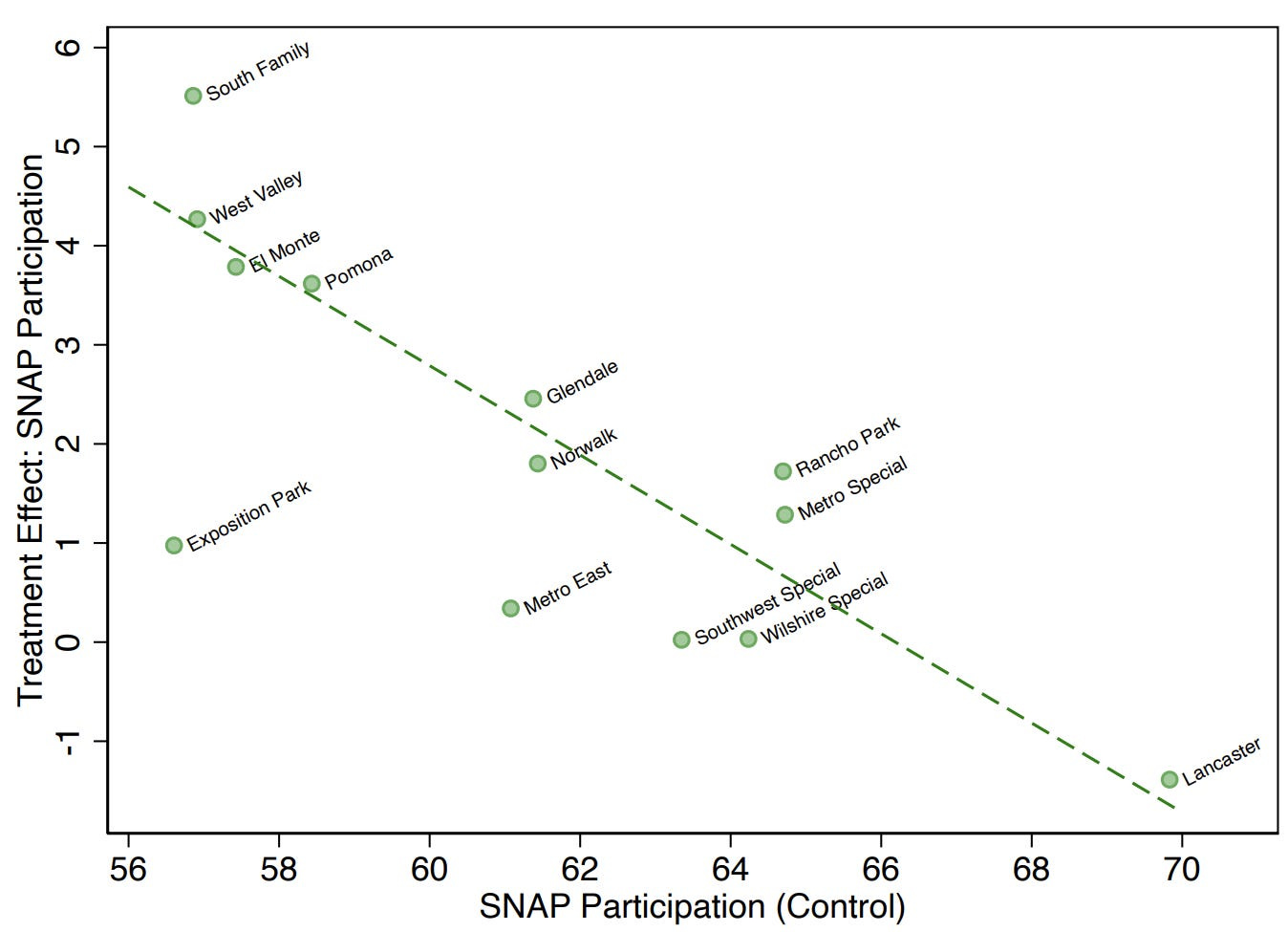

Finally, in Los Angeles, the flexible interview process reduced disparities in access across offices. While we cannot control for all the eligibility, geographic, and resourcing factors at play – in general, the offices that had comparatively low enrollment rates among applicants saw the largest gains from the flexible interview process (Figure 3). In other words, flexibility can sometimes mitigate disparities due to bottlenecks in the system.

Figure 3: Flexible interviews reduced variation across offices in eventual enrollment among SNAP applicants (Los Angeles)

One important caveat is that flexible interviews as a strategy depends upon having sufficient administrative and change management capacity. This does not necessarily mean more administrative resources, as it seems flexible interviews may well be able to improve efficiency. But it means that, at a minimum, the roll-out should ensure clients who call anytime can actually get through to a human being. For example, as Dave Guarino notes, the state of Missouri was sued by SNAP advocates when its “on demand” SNAP interview process was effectively denying access to tens of thousands of clients who were unable to reach anyone. In contrast, in Los Angeles, call wait times remained around five minutes or less during the transition thanks to a careful and gradual roll-out, accompanied by daily monitoring of key metrics by supervisors and leadership. The gradual roll-out with close monitoring helped to identify resourcing and process iterations that enabled the new approach to be successful.

For state and local governments serious about reducing burdens both on employees and applicants, flexible interviews represent a proven tool.

Eric Giannella is Associate Research Professor at the Georgetown Better Government Lab where he helps non-profit and government organizations identify ways to improve access to safety net services. Previously, he was the Senior Director of Data Science at Code for America.

It's so frustrating when people design systems but seemingly have no idea how their designs affect the people who have to use the systems. I'm a retired academic and associate dean. Years ago, my university began to use the educational platform Blackboard, and they allowed users to create an account using any email address. After a couple of years, about two weeks before the fall semester began, IT decided to require users to have a university email account. I had to call an emergency meeting with each of the associate deans, IT and the Provost to explain that graduate students in the business school (which had the majority of part-time graduate students) didn't have a university email account because IT required them to come to campus, during the day, and apply for one. IT was surprised and had no idea why this was a problem. Undergraduate emails were automatically generated for 1st year and transfer students. After an hour or so, we all agreed that a university email account would be generated for each graduate student when they registered for a course for the first time. I ran into this issue numerous times over the years because the people designing the systems never use the systems so they're unaware of the problems.