When Russia attacked Ukraine, many were surprised by how effectively the country responded. One aspect of that resistance was Ukraine’s digital capabilities. In a new paper published in Public Administration Review, we explain how Ukraine built what we label as digital resilience, the use of digital government capacities to maintain basic societal functions in crisis situations. One of us (Gulsanna) has been directly involved in these efforts, currently serving as an adviser to the Deputy Prime Minister on Digital Transformation, Innovation, Science and Technology of Ukraine.

Prior to the war, Ukraine upgraded its digital government capacities. The war provided the impetus to speed up the use of those capacities, which were used not just for defensive military purposes, but also to provide continuity to the civilian aspects of government, including the provision of digital documentation and aid to displaced people. In doing so, digital capacities provided a key basis for Ukraine's resistance.

President Zelenskyy campaigned on a “state in a smartphone” platform. The vision was to build a convenient digital administrative state, one which minimized paperwork, bureaucracy, and opportunities for corruption. The reference point was frictionless service delivery of private technology companies such as Uber or Airbnb, while reflecting the shift to “government as a platform” that Tim O’ Reilly has articulated.

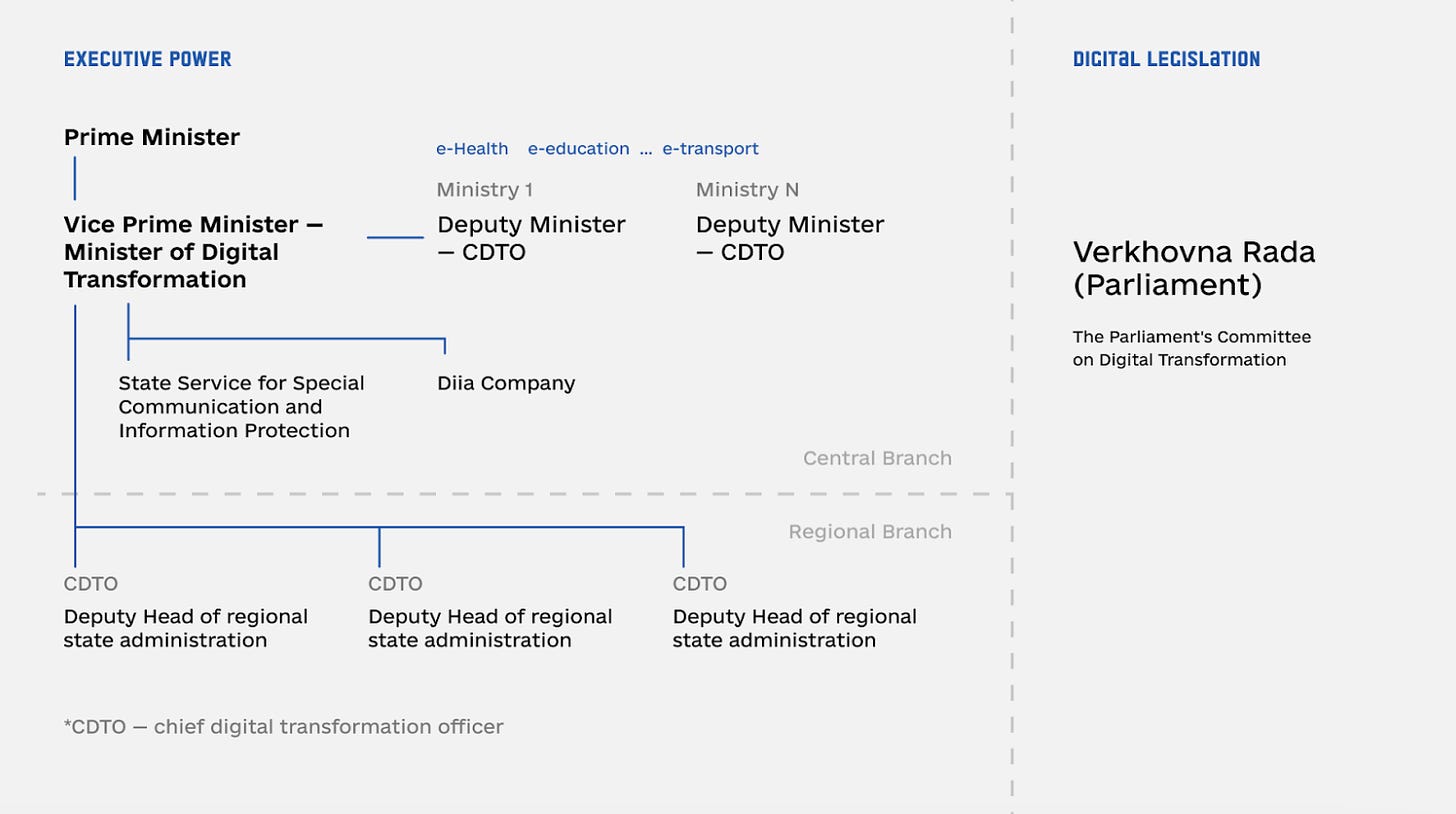

The most tangible structural outcome of Zelenskyy's vision was the creation of the Ministry of Digital Transformation in 2019. The creation of a stand-alone ministry provided a visible commitment on the part of the President, as did the appointment of the Deputy Prime Minister, Mykhailo Fedorov, to run it. Fedorov was a young founder of a start-up who entered government, rather than a veteran politician adding digital to his responsibilities. In addition to the ministry, a system of chief digital transformation officers (CDTOs) was established. The goal was to create a CDTO responsible for digital transformation at every agency on the central and regional level, meaning that the impetus for reform was not limited to a single ministry. As the result of this institutional structure, the capacity of the state to enable the cross-sectoral digital transformation was set.

2020, “Diia” was introduced. In Ukrainian, Diia means “action” and is an acronym means “state and me.” Diia's digital ecosystem included a mobile application with digital documents and most popular public services, a government portal for other public services, an education project for the development of digital skills and literacy, and projects to facilitate small and medium-sized enterprise and IT companies. Drawing on examples from other countries, the government prioritized public-facing services that could be delivered in a digitalized or digitally enhanced mobile-based fashion, reflecting a human-centered approach to digital service delivery. These included applications for housing loans, submitting tax declarations, paying taxes, a Covid-19 vaccination waiting list, and application for financial assistance. More than 25 public services are available in mobile application and more than 90 public services on the government web portal. The number of services available is constantly being expanded.

A shift to a digital system of service delivery creates the risk of a digital divide, where those with lower digital literacy are excluded. Ukraine’s government worked proactively with citizens to improve their digital skills and their willingness to adopt the solutions offered by new technology. The government also sought to reduce learning costs by making digital interactions work through a single, branded, and therefore recognizable interface of Diia.

Thematically, Diia centered on reducing administrative burdens for citizens and businesses, part of the broader political strategy to allow Ukraine to more rapidly develop while shrinking the size of its bureaucracy. Diia allowed citizens access to and digital versions of basic documents: national ID card, passports, student ID, driver's license, vehicle registration certificate, vehicle insurance policy, tax number, migrant certificate, COVID certificate, and pension certificate. Indeed, Ukraine became the first country in the world with a digital passport that served as full legal analog of ordinary physical documents and the fourth country in Europe with a digital driver's license. Citizens could perform basic service interactions, such as registering a newborn. Nearly 19 million Ukrainians use Diia mobile application and about 22 million use the web portal, out of an adult population of 33 million.

Diia also serves businesses, offering rapid business and company registration and a one-stop-shop portal for entrepreneurs. Diia.Business provided free consultations and training on about 70 topics (legal, taxation, finance, HR, marketing), and access to financial support programs. Business support centers for SMEs were opened across Ukraine. Diia.City introduced a unique legal and tax framework for IT companies. More than 450 companies received Diia.City resident status and the number continues to grow even during the war.

INNOVATION DURING THE WAR

Technology can be a force of change, generating deeper and more meaningful reconfigurations of public services over time. The speed of the embrace and application can vary. The Ukraine case shows how crisis sped up and drew upon an existing process of innovation. Strategies that had been subject to debate and adaptation were now quickly embraced. Understanding this embrace requires understanding two aspects of Russia's attack. First, it combined both traditional kinetic elements, such as soldiers and munitions, with cyber warfare. Second, the attack was not limited to military targets but also included civilians and civilian infrastructure. This made digital capacities an essential tool in responding. We identify six major innovations that took place.

Protecting digital infrastructure and communication

Russia constantly conducts cyber and physical attacks on the country's digital infrastructure, including satellites, telecommunications stations, and Ukrainian government computers. A missile partially destroyed the Ukrainian government's main data center in Kyiv. Russian precision strikes have deliberately targeted broadcast towers. Such attacks reflect the centrality of internet connectivity to government continuity, which gains heightened importance during war, as well as other extreme situations such as natural disasters. In particular, digital technologies have played a crucial role in providing citizens with reliable information from the government, as well as access to digital services, essential ingredients in societal resilience.

Ukraine protected critical facilities in different ways. The government switched to satellite internet technology to ensure a stable internet connection for critical infrastructure, including medical, energy, education, and business facilities. Ukraine has the largest number of Starlink terminals, with about 30,000 terminals, most of which were donated by SpaceX company, EU countries, and partners. The government also helped to restore communication in Irpin, Bucha, Borodyanka, and other regions after their de-occupation.

Protecting administrative data

Prior to the war, Ukraine had invested in using open administrative data. Once the war began, datasets that could potentially be used by the enemy and harm the interests of national security were temporarily removed from public access. Ukraine continues to publish and update datasets that do not threaten national security.

In preparation for the cyber and physical attacks against the country's information infrastructure, the government amended Ukrainian data protection laws to allow the government to store and process data in the cloud and work closely with several technology companies, including Google, Microsoft, and Amazon, to transfer critical government data to infrastructure hosted outside the country. This action had been previously considered but not acted upon by Parliament. The war gave a new logic and impetus for the change, since the country could no longer guarantee the security of physical locations.

Co-production of defensive efforts

With the advent of the war, the Ministry of Digital Transformation transitioned to a more military role. They successfully lobbied both large and private small technology firms to aid with Ukraine's defense, by restricting access to satellite information to civilian movements, winning access to Starlink terminals, Google workspace licenses, and limiting the reach of Russian misinformation. The Ministry lobbied for a digital blockade of Russia, by lobbying tech companies to leave the Russian market.

The government also used digital means to facilitate citizen co-production in the military effort, building on existing tools. The eEnemy Telegram chatbot was launched, open only to authenticated accounts from Diia, minimizing the risk of disinformation. The tool allows its 500,000 users to send geolocation, photos, and videos of the Russian army's equipment with the opportunity to describe what they saw in the text. The data are transferred to the Ukrainian military. The bot was later updated to allow reporting the location of explosive objects, speeding the disposal of mines, projectiles, and bombs left by the invaders. It also allows citizens to collect and share contemporaneous data of war crimes by occupiers, data that are otherwise difficult to collect in occupied domains. This functionality reflects how tools, such as Ushahidi platform in Kenya, allow individuals to report information during disasters and to protect human rights.

Providing documentation for displaced persons

About one quarter of Ukranians were displaced within a month of the war's beginning. More than 9 million Ukrainians fled the country since the beginning of the war. The largest displacement of people in Europe since World War II created a need for portable and internationally interoperable digital solutions to help people prove their identity, despite the frequent loss of physical documentation.

Digital documentation was widely accepted within Ukraine and on an ad-hoc basis by local law enforcement and border guards of neighboring countries. Ukraine worked with neighboring countries to explain how Ukrainian digital documents work and how integration scenarios of validation (checking the document's validity) or sharing (receiving the PDF copy of the digital document) could be implemented. When countries were reluctant to harmonize their document policies, a temporary solution was offered. Ukraine allowed other authorities to check information on digital driver's licenses directly from the registry of driver's licenses.

Such advances would have been impossible without the prior efforts made to develop digital documentation. Other countries are importing some of these techniques, including leaders in digital government. For example, Estonia is working to launch the government application mRiik, based on the Ukrainian Diia. In its initial trial phase, mRiik will allow Estonians to digitally store critical documents such as ID cards, passports, and driving licenses and access some public services.

Maintaining state benefits for citizens

Despite its challenges, the Ukrainian government has expanded its effort to provide digital public services. Indeed, it used digital services to compensate for the challenges of using in-person services created by the destruction of physical infrastructure and displacement of citizens. Diia offered a proven instrument in responding to the needs of citizens and businesses dealing with the consequences of the war.

Diia was crucial in keeping track of and communicating with Ukrainians fleeing war-affected regions and helping them access critical public services while displaced. After the war began, nearly half a million people self-registered as internally displaced and accessed the online services and other assistance, including monthly cash assistance from the state to address the humanitarian needs of their families. Providing quick and easy access to cash reduced the severity of need for displaced people. This offers a stark contrast to the standard problem of providing aid in crisis situations, which is that displaced people lack the documentation needed to overcome the administrative burdens to receive state supports.

Adapting Diia to the needs of displaced people during a war was a considerable challenge. Even so, new services have been introduced such as buying military bonds through Diia, contributing to a government initiative to raise funds for military and medical equipment, a program of financial assistance to entrepreneurs and employees from the regions where hostilities took place, applying for compensation for damaged property, TV and radio access to news, e-pension certificate, accessing car registration certificate to transfer the right to drive the vehicle, driver's license renewals, receiving a court decision, and changing of residency.

Diia.Business centers also provide help to displaced people. For example, a mother who fled to the Czech Republic with her children can ask for help finding local kindergartens and schools. A pregnant woman who left Kharkiv for Warsaw to give birth can ask about social guarantees. There are thousands of such requests.

Maintaining economic activity

Financial assistance was also offered via Diia to entrepreneurs and employees from regions where hostilities took place. The place of registration and place of work was checked automatically online. Almost 5 million applications were received, and $867 million was paid. Just as the war pushed politicians to embrace digital solutions, it gave citizens strong incentives to adopt new technologies.

The government also launched a virtual Diia.Business center for Ukrainians abroad, where they can get help finding a job, opening a business, or temporarily moving their business. Internally displaced persons in Ukraine can also receive consultations. For instance, the center advised people looking for an opportunity to leave Mariupol for Poland by car without documents and needed help with free housing, applying for and receiving social benefits, and employment.

What happens next?

Smart technologies make new forms of service delivery possible, but also have implications for how bureaucracy is organized. The war put the Ukrainian government in a period of forced innovation, which will have long-term consequences. Prior to the war, technology was a growing part of the Ukrainian economy, and central to the vision of reforming government. Even as the war progresses, it has become even more central not just in helping the country defend itself and mitigate the effect of attacks, but also in the future that Ukraine sees for itself. Part of those plans include moving ever more public services online, expanding both digital access and literacy, building security around digital resources, and making digital a key component to accountable and transparent rebuilding and recovery efforts. It will also require a period of post-conflict re-evaluation of those innovations to make them consistent with traditional modes of public accountability.

Gulsanna Mamediieva is a Fellow at the Better Government Lab, and a Tech and Public Policy Fellow, at Georgetown University. As former Director General for European and NATO integration at the Ministry of Digital Transformation of Ukraine, she played a key role in Ukraine's rapid digitalization transformation. She currently serves as the CEO of Digitality.Gov Tech Center of Excellence, non‐profit focused on advancing the digital transformation of the public sector.

This is amazing. I had absolutely no idea about the digital innovations that Ukraine developed and are using. I knew about the drones, and the problems with Musk and Starlink because those have been reported on, but nothing about the day-to-day digital operations. So much of this will be so helpful not only in Ukraine but around the world. Thank you for distilling this information.