The longer the pandemic goes on, the more trust will decline in institutions that have to make visible, salient decisions amidst changing circumstances, information and trade-offs while serving a population with wildly varying preferences.

This somewhat depressing insight may or may not seem obvious to you, but it wasn’t apparent to me until recently. The emergence of Omicron, which will propel us into a third year of the pandemic, and growing liberal dissatisfaction with the Biden administration helped crystalize this realization. My thinking on this is based on fitting what we know about certain biases (motivated reasoning, negativity bias, hindsight bias) on the dynamics and longevity of the pandemic.

As the pandemic continues, a series of forces will combine to reduce faith in political institutions. The third year of the pandemic will be extraordinarily damaging.

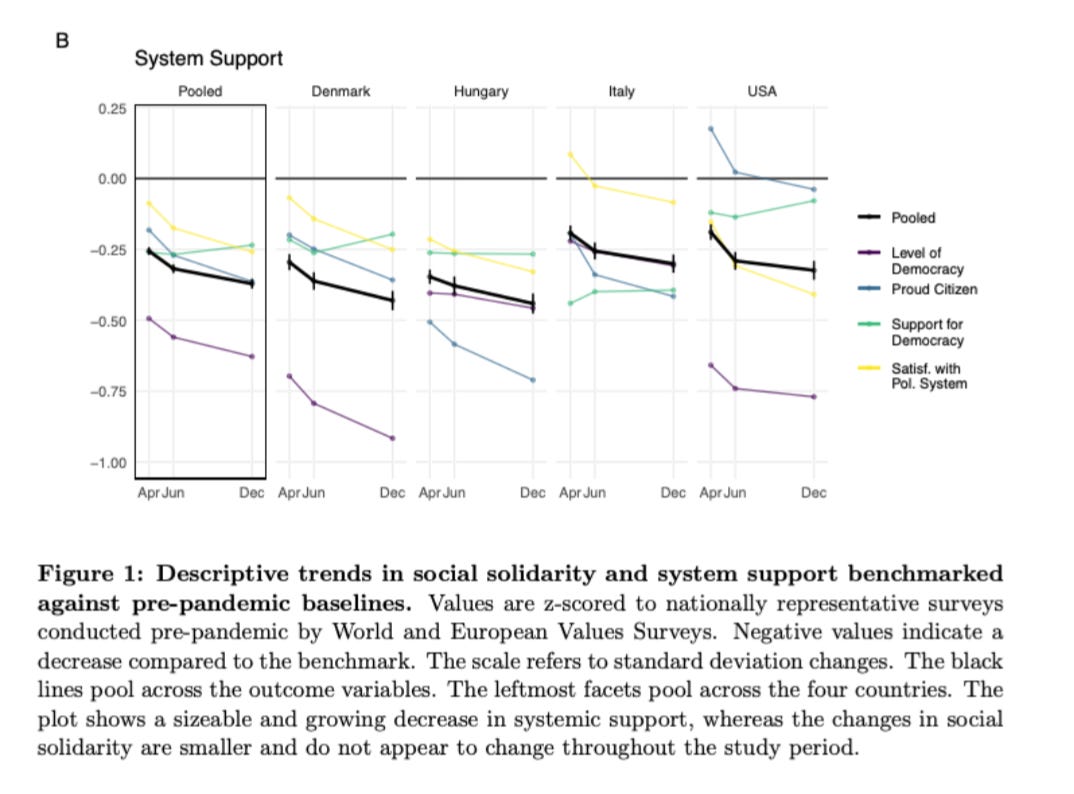

First, some empirical evidence: a team of scholars from Aarhus University (Alexander Bor, Frederik Juhl Jørgensen, and Michael Bang Petersen) tracked public opinion of 6,000 people across four fairly different countries (USA, Italy, Denmark and Hungary) in 2020.

The good news: trust between citizens remained relatively stable. We are not at each others throats!

The bad news: satisfaction with the political system declined in each setting, as did the sense that the country was being governed in a democratic fashion.

So why is the erosion of trust inevitable?

Motivated reasoning and its limits

We tend to uncritically give credit to the performance or politicians we agree with, and blame those we disagree. This bias creates both a floor and ceiling for trust. Some people will support Biden or Trump no matter what they do. Some will oppose.

A new article by Julie A. VanDusky-Allen, Stephen M. Utych and Michael Catalano, provides evidence of both motivated reasoning and its limits. They show that the public tended to be more generous to their governor’s pandemic response if the governor was a co-partisan. But they also showed that Democrats did not rely on partisanship to the same degree as Republicans in evaluating Covid response. After the first wave of shutdowns, when states were re-opening, Democrats also responded to how closely state policies reflected their policy preferences.

People now have pandemic preferences

In February of 2019, few of us had really well-thought-out preferences about face masks, school closures, vaccines or vaccine requirements, and the degree to which they are necessary in the context of a health crisis unlike any we had ever encountered. Now, we do. As the pandemic has gone on, those preferences have hardened. People now talk about Covid hawks (those who favor aggressive public health restrictions) and Covid doves (those that don’t), as if it’s some fixed political identity.

These preferences will be in no small part driven by ideology, but as the VanDusky-Allen et al. paper shows, Democrats are willing to make evaluations about political performance based on their pandemic preferences, and not just ideology. This is good for Republican incumbents whose public health guidelines match with those preferences, but bad news for Democratic incumbents whose policy decisions are at odds with their supporters.

As the pandemic continues, perceived failures by the White House, FDA or CDC will be questioned not just by conservative critics but also by liberals who think of themselves as pro-science. Obvious examples are the scarcity of tests, the lack of a vaccine mandate to fly, or revised CDC quarantine guidelines. On the latter, some people regard a five day isolation period to be unsafe, some do not. I don’t know what the right answer is. Lindsay Leininger of Dear Pandemic makes a good case that the guidelines are an example of policymakers wrestling with real tradeoffs, and different people are interpreting those tradeoffs differently. But the point is that many view the decision as a policy failure, and increasingly doubt the credibility of the CDC. Type “CDC” on Twitter, and you are likely to get a series of gags as much as you are to get health advice.

Negativity bias

Loss aversion means we are more attentive to and emotionally aroused by loss than gain. Apply that insight to public policy, and you get negativity bias, where people take good performance for granted, but are angry about what they see as bad decisions or outcomes.

The key implication is that institutions who are put in the spotlight where they have to make salient decisions will draw more blame than credit. The longer they are in the spotlight, and the more decisions they have to make, the more blame they attract. The potential for blame also increases where there are few opportunities for credit claiming. With a pandemic, pretty much everyone is worse off. People are angry about restrictions on their movement, closed schools, or wearing masks. Other people are angry at decisions that reduce safety without seeing offsetting the benefits. Anger and frustration are the salient emotions.

None of this is to say that governments don’t make real mistakes. Faced with novel challenges where they have to respond without a blueprint, failures are inevitable. An exasperated spokesperson says something tone-deaf (e.g., Psaki mocking the idea we should send everyone home tests). Or countries over-regulate, e.g. suspending vaccines due to rare cases of side effects, thus increasing vaccine hesitancy. But negativity bias means that the mistakes loom larger in our memory than the successes.

Hindsight bias

Another bias that shapes our views of public institutions is that we impose a filter on past decisions that understates the complexity of those decisions. With the benefit of hindsight, we persuade ourselves that the right answer was obvious all along. Malcolm Gladwell’s discussion of the assumption that intelligence agencies should have been easily able to “connect the dots” about the looming 9/11 attack is a great practical example.

Thus, we not only pay closer attention to the failures, we are persuaded that the failures should have been easily anticipated. For example, the Biden administration focus on vaccines and relative neglect of testing capacity last summer now looks like an obvious miscalculation because of Omicron, but wasn’t widely covered as such at the time.

Messaging inconsistency

A basic function of public leaders in a crisis is to communicate simply and clearly, and to convey reassurance. But it is also their job to adapt to changing circumstances. Over time this balancing act becomes less and less sustainable. Consistency in messaging and adaptability are at odds with one another. Both acknowledging errors or denying them sap credibility. It’s easy for critics to claim you are moving the goalposts, even if you are simply adapting to new realities.

Fatigue: We are all exhausted

The Aarhus University study discussed above examined what factors were associated with declining trust in the political system. The key answer was pandemic fatigue. As people felt the pandemic as an unbearable burden, or experienced a sense of anomie, their trust in the political system declined. Pandemic fatigue led people to express more extreme anti-system attitudes and lean towards populism. In the US, people have turned to turn to conspiracy theories to offer answers to an unprecedented set of challenges.

That sense of fatigue has eroded our willingness to give public institutions the benefit of the doubt. Some leaders seemed able to maintain a sense of solidarity— New Zealand’s Jacinda Ardern being the outstanding example. Such unity never really existed in the US, partly because President Trump made only a half-hearted effort to draw upon it. But even in the best of circumstances, solidarity fades. Calls for shared sacrifice ring increasingly hollow. In Ireland, Seamus Heaney’s aphorism “If we winter this one out, we can summer anywhere” was used by politicians to convey the need for temporary sacrifice. Almost two years on, it’s as likely to generate eyerolls and revisions like “If we winter this one out, then we can winter again next year and the year after.”

Will trust recover?

If you are concerned about trust in government, all of this probably sounds fatalistic. The causes pandemic-related distrust that I’ve outlined are generic, and apt to arise for any institutions with responsibility for and accountability to the public, though local conditions will affect the nature and extent of the damage.

An important caveat is that I am not saying that government performance does not matter. It does. Or that public accountability is bad. It’s not, and we certainly need in-depth evaluations of the US public health system from top-to-bottom to learn lessons for the future. Instead, the point is that the pandemic has put public institutions in a domain where they are going to lose credibility, and has done so for such a sustained period of time, that the damage is severe.

Are there any reasons for hope?

One source of insight is cross-time Pew survey measures of agency popularity. What this shows is that a) individual agencies are more popular than “government” as a whole, with many more people having favorable than unfavorable views, b) favorability does move with real-world perceived failures, e.g. attacks on the IRS and VA during the Obama era led to declines in favorability for those agencies, but c) tend to bounce back to some previous baseline level of favorability when out of the spotlight.

Its possible therefore that faith in some institutions will not be affected, and faith in specific institutions like the CDC and FDA will bounce back to pre-pandemic levels at some future point. But my guess is that the scale of the pandemic means that the bounce-back will take a long time, and for some people, will never happen.

I very much hope I am wrong. I hope that liberal democracies can weather such a stress test. Maybe Omicron will, as many hope, signal the beginning of the end.

What worries me most is that countries with existing fault-lines are vulnerable to a cascade effect. In the US we have an anti-institutionalist media and political elites that actively sow doubt and undermine collective action. Declines in institutional trust will further fuel the ongoing rise in populism, as some look for a facade of strength to offer a false reassurance of competence. If this is correct, the stakes of the pandemic are bigger even than the already enormous health and social disruptions.

If you found this post useful, please check out the archive, consider subscribing if you have not done so, and share with others!

I find myself wishing I didn't agree with you Don. While this is a bummer going into a new year, I think the analysis is spot on and an effective mixture of public opinion, public policy with cognitive bias.