Administrative Backsliding Accompanies Democratic Backsliding

Warning signs from other countries about politicization of the administrative decline

From Don: This is a guest post from Professor Kohei Suzuki, a scholar of civil service systems around the world. Here, he points to evidence that the Trump administration’s assault on civil service systems is part of broader pattern: where there is democratic backsliding, there is also administrative backsliding. Administrative backsliding involves abandoning norms intended to serve democratic states — such as merit, expertise and nonpartisan service — and replacing them with norms such as politicization, and centralization of power.

The second Trump administration has initiated unprecedented change to the federal civil service system. On inauguration day, Trump established the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), launching a dramatic transformation of federal workforce management. Within its first month, the administration has implemented a three-pronged strategy: a near-total hiring freeze, a deferred resignation program, and widespread terminations without regard for individual performance or position criticality. The scale and speed of these reductions are without precedent in American administrative history.

A controversial aspect of these changes, yet to be fully implemented, is the "Schedule Policy/Career" classification, a revised version of Schedule F that would create a new category of readily dismissible political appointees. This change could expand the number of political appointments more than tenfold, affecting at least 50,000 federal employees. These reforms reflect Trump's first-term experiences, where he viewed his policy agenda as impeded by what his allies termed the "deep state" - career civil servants resistant to his directives. The administration's clear aim is to force career bureaucrats to be more aligned with its agenda, or remove them.

Such changes raise serious concerns about the long-term consequences for bureaucratic autonomy and institutional capacity. What does the research tell us about whether Schedule F will truly create an "efficient government" and “make America great again” as Trump claims, or will it instead undermine the professional foundations of American public administration?

To address this question, we must consider why professional bureaucracies are essential to modern governance. Effective policy implementation requires both political direction and administrative expertise. While elected officials establish broad policy goals, they lack the specialized knowledge needed for the thousands of technical decisions that government operations demand daily. Career civil servants bridge this gap, providing the expertise and continuity necessary for effective public service delivery.

Career civil servants' expertise becomes evident when we examine the complex tasks of modern governance. Daily operations include activities like collecting pension premiums, analyzing economic data, implementing financial regulations, and managing defense procurement. These functions demand not just specialized knowledge but years of practical experience and institutional understanding - qualities that cannot be rapidly replaced or replicated.

The effective functioning of democratic governance thus depends on a careful balance: elected officials provide policy direction while professional bureaucrats handle technical implementation. Critical decisions - from monetary policy to drug safety certification - require deep technical expertise rather than political judgment. When politicians overreach into these technical domains, their limited specialized knowledge and focus on short-term political gains often leads to suboptimal or even harmful outcomes.

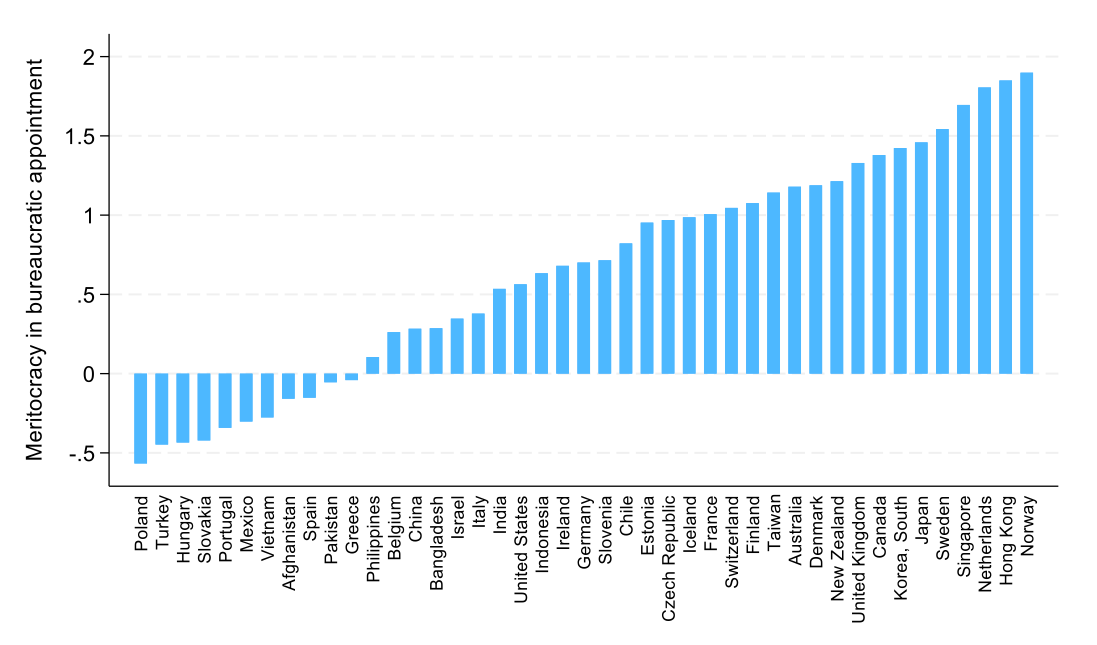

While the need for professional bureaucracy is universal, countries vary considerably in how they balance political leadership and administrative expertise. A 2020 expert survey by the Quality of Government Institute at the University of Gothenburg measures how strongly governments adhere to merit-based principles in their personnel practices. The data reveals significant variation across OECD member and Asian countries and regions, with higher scores indicating stronger merit-based practices and correspondingly lower levels of political intervention in personnel decisions.

Figure 1: Degree of meritocracy in bureaucratic personnel matters among OECD member and Asian countries

Under merit-based systems, civil service appointments primarily depend on educational background and professional experience rather than political connections. Countries like Norway, Hong Kong, the Netherlands, Singapore, Sweden, and Japan have developed particularly robust merit-based practices. The American system stands out especially among developed nations for its relatively extensive use of political appointments higher degrees of political interference in personnel matters.

The contrast becomes stark when comparing specific numbers: while Japan maintains only about 80 political appointments in its entire civil service, the United States replaces approximately 4,000 high-ranking positions through political appointments during administrative transitions. Such high degree of political influence in personnel matters has long distinguished the U.S. federal bureaucracy from its counterparts in other advanced democracies.

The extensive use of political appointments in the U.S. federal bureaucracy reflects a broader phenomenon that public administration scholars term "politicization" - the practice of basing civil service personnel decisions on political criteria such as party relationships, personal connections, or ideological alignment rather than merit criteria. The US already lagged most other countries in its use of merit-based practices even before the dramatic changes being introduced under the second Trump administration, which will significantly expand politicization.

The consequences of such politicization have been extensively studied. A robust body of research, drawing from diverse national contexts including both developed and developing countries, demonstrates that increasing political control over bureaucracy tends to undermine, rather than enhance, government performance. Empirical studies around the world have found strong correlations between excessive politicization and increased corruption, decreased organizational performance, and reduced operational efficiency.

In fact, our recent systematic review of over 1,000 peer-reviewed papers provides compelling evidence that merit-based systems yield significantly better outcomes than politicized ones, including reduced corruption, improved efficiency, increased public trust, and enhanced civil servant motivation.

New research with Victor Lapuente, "Politicization, Bureaucratic Legalism, and Innovative Attitudes in the Public Sector", examines how institutional characteristics of bureaucracies shape innovation capacity in government organizations. Using data from over 5,000 senior public managers across 19 European countries, we investigated how politicization in administrative systems affects managers' willingness to embrace innovation and change. We found that politicization—the extent to which career advancement depends on political connections rather than merit—significantly diminishes public managers' pro-innovation attitudes.

Our analysis revealed a clear pattern: as the level of politicization increases in a country's bureaucracy, senior managers demonstrate progressively lower receptiveness to new ideas and creative solutions.

The research highlights how public managers' motivation to innovate is fundamentally shaped by their labor market conditions. When managers operate within merit-based systems where their future career prospects depend on performance rather than political allegiance, they show substantially greater willingness to pursue organizational change and implement new approaches. Conversely, in politicized environments where career advancement hinges on political considerations, managers become increasingly resistant to disrupting the status quo, ultimately prioritizing the satisfaction of political superiors over meaningful organizational improvement. This may be because that politicized systems are driven by political logics of blame avoidance and defensiveness, whereas innovation requires some measure of protection for experimentation.

In light of these findings, its worth looking at public sector changes within a broader global context. Public administration scholars have increasingly focused on how populist politics affects bureaucratic capacity and civil service performance. This research has identified a pattern that the political scientist Michael W. Bauer terms "administrative backsliding" (echoing the term democratic backsliding): the systematic weakening of bureaucratic institutions in countries experiencing democratic decline.

The changes in the United States share striking similarities with changes implemented in several other countries: Hungary under Orbán, Brazil under Bolsonaro, Turkey under Erdogan, and Venezuela under Chavismo-Madurismo. These cases reveal consistent patterns: weakening bureaucratic autonomy, concentrating executive power, and undermining administrative institutions through budget cuts, personnel changes, and information control. Most notably, evaluation criteria shift from professional capability to political loyalty, often resulting in politically motivated dismissals or transfers.

The consequences of such reforms are well-documented. Brazil's experience shows how political appointees lacking adequate expertise decreased administrative efficiency. In Hungary, politically motivated personnel decisions demoralized civil servants and led to a critical loss of organizational expertise. In Turkey, the Justice and Development Party (AKP) governments intensified anti-bureaucratic rhetoric, framing the bureaucracy as an extension of a privileged elite. This framing reinforced the populist dichotomy between the "pure nation" and the "enemy of the nation," positioning the AKP as the true representative of the people while portraying the bureaucracy as a "servant of a specific elite group" and, consequently, an "enemy of the people". Similar patterns emerged during Trump's first term, where expert staff were often viewed as "political resistance forces," leading to a devaluation of expert judgment and loss of organizational expertise as experienced staff resigned.

For supporters for Trump, radical bureaucratic changes, can be understood as both a response to problems within existing bureaucratic systems and a reflection of public distrust in bureaucracy. However, excessive politicization of bureaucratic systems compromises administrative expertise and autonomy, risking a long-term decline in policy implementation capabilities and public service quality. Achieving better quality of government requires operating bureaucratic systems under appropriate political control without excessively weakening them, while leveraging their expertise. American public administration and practitioners should take heed of the experiences of countries that have faced administrative decline.

Kohei Suzuki is an Assistant Professor at the Institute of Public Administration, Leiden University, and holds the title of Docent in Political Science at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. His research focuses on bureaucratic behavior, quality of government, and administrative reform from a comparative perspective. Recently, he led cross-national experimental surveys of local civil servants in Japan, Sweden, and Spain. His research has been funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) and Swedish Research Council, among others. Website: https://koheisuzuki.weebly.com/.

This editorial is a revised and expanded version of an article published in the Nihon Keizai Shimbun and the Asia Pacific Journal of Public Administration.